Sustainability

Truth and transparency – sustainability meets credibility in 2022

Food companies will find it increasingly hard to talk about their sustainability while swerving the detail, writes David Burrows.

S

ome of the world’s largest consumer goods companies this week agreed to change their US recycling labels following a lawsuit based on unlawful and deceptive claims. Consumers had been misled, suggested US campaign group The Last Beach Cleanup (LBC), because they were not told about the limits on the TerraCycle programme involved.

“This stinks,” raged one environmental consultant on LinkedIn. LBC was more restrained: “[…] shareholders and consumers must demand that companies report on the credibility of their recycling claims and adopt real solutions to stop the global plastic waste and pollution crisis.” This was about “truth and transparency”, wrote Jan Dell from the group in an email.

Food brands would be wise to keep those two words front of mind as sustainability meets credibility in 2022. Whether it is innovation on cultivated meat or plant-based proteins, the use of recycled content in plastic packaging or carbon reduction commitments aimed at net zero, brands will above all else have to be transparent. Think genuine rather than greenwash. Think honesty over hype.

Foot(print) race

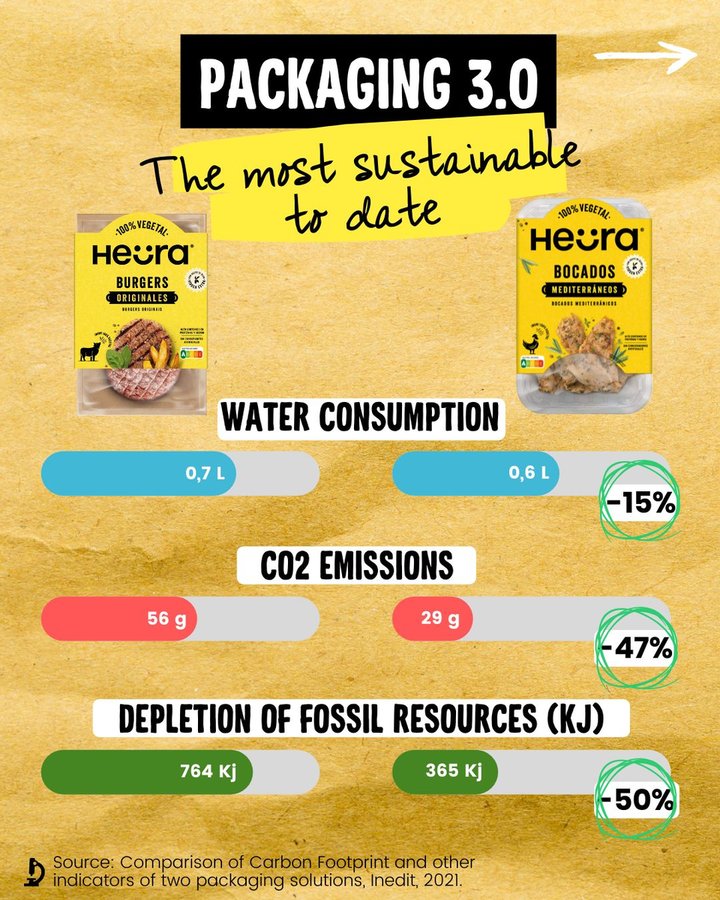

Some companies are already reacting to this. Heura Foods, the Spanish plant-based protein business, has just changed its packaging in its home market. On social media it shared its journey from using plastic, then a switch to paperboard and now back to plastic. Returning to plastic – a much-maligned material – is a brave move. “We know it’s not the perfect solution but it’s the best one yet,” the company said, citing the results from a life cycle assessment (LCA).

Credit: Heura Foods om LinkedIn

LCAs are in vogue. More and more brands will use them to explain (or justify) their decisions. In some countries, like the UK, regulators now want to see the science behind any green claims being made, including ecolabels. These are promoted as the sustainability stars of supermarket shelves as brands look to tap into carbon-conscious consumption. “Carbon is strongly associated with food sustainability by consumers, but it currently has a limited influence on consumer choice,” noted Bord Bia, Ireland’s state-run, food-promotion agency in recent research. The study involved more than 11,000 consumers in 13 markets, experts and food companies like Kellogg, General Mills, German meat giant Tönnies and Tesco.

Schemes are popping up all over the world: some are precise, taking more time and money; others are less so but have already been rolled out rapidly to tens of thousands of products in France, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK. Carbon numbers and eco-scores will “change the game”, Bord Bia claimed – but it won’t happen overnight – or even in 2022.

Whether a label is enough to change behaviour is moot. It is not a silver bullet and some food companies are already complaining they spend more time counting carbon than cutting it. Consider, too, how many years it is taking to agree on an approach for nutritional labelling for markets like the EU (counting calories is far easier than counting carbon, or indeed chemical use and the biodiversity impacts of everything from a pizza to Parma ham).

Green intentions

Brands should be wary shoppers want help to make better choices. Many are frustrated the intention-action gap on sustainable choices isn’t closing fast enough. Research among 30,000 people in 31 markets just published by Globespan (and supported by PepsiCo, WWF and others) showed 47% want to change their lifestyle “a great deal” to be more environmentally friendly but only 23% have made major changes in the past 12 months. Some 60% say the same about being healthier, yet only 28% have done something about it.

So consumers are counting on more information – from carbon to calories. Manufacturers of plant-based products have been keen to expose the former but should expect more scrutiny next year on the latter. Ultra-processed food will be under the spotlight next year. Expect hard-hitting scientific research, more investor activism targeted at big food brands and supermarkets; plus prying from campaign groups and concern rising among consumers.

Demand could well polarise around better products: better for you and better for the planet, because people want both. This could see ‘forgotten’ crops embraced, ‘ethical dairy’ gain traction and the debate around ‘better’ meat come to a head.

Control Room in Upside Foods Engineering, Production and Innovation Centre

Credit: Upside Foods

With net-zero high on the agenda there will be plenty to chew over when it comes to meat next year: from the sustainability of traditional livestock to the sexier topic of lab-grown chicken and beef. In 2020, US$366m (EUR317m) was raised by cultivated meat companies (six times that in 2019), with 70 companies working on at least 15 different types of meat. Those involved should take nothing for granted as critics of their ambitious plans – as well as their environmental claims – grow.

Alternative proteins are exciting but whether it is lab meat, insects or algae many producers remain secretive. That will do little to convince consumers, so brands will set about making these novel products appear normal.

Take Upside Foods, a food tech company headquartered in California which has just opened an “engineering, production, and innovation centre”. There are big windows into production rooms and the bioreactors making its cultivated meat products. A launch video is at pains to highlight that the facility is in a “vibrant urban setting surrounded by neighbourhoods and eateries”. The message is: “Our doors are open.”

Nothing to report

Transparency, Upside knows, will be key to consumer (and regulatory) acceptance. Any brand will find it increasingly hard to talk about their sustainability while swerving the detail. A small study of 46 food companies done by Yale School for the Environment in March showed “a lot of effort going into appearing to be a good actor, but these efforts were rarely externally verified”. In other words, greenwash.

Brands that end this year thinking net zero makes them a hero could face a long hangover in 2022

A staggering number of food companies still say nothing on sustainability. Experts at the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) this year picked through the strategies of the world’s largest food and agriculture companies: more than one in four (27%) of the 350 firms failed to disclose any sustainability strategy at all. “We have a lot of companies that are not reporting on key themes, including on greenhouse gas emissions,” WBA research lead Sanne Helderman told Just Food. Just 26 (7%) of the 350 had set greenhouse gas emission reduction targets aligned with the Paris Agreement.

In 2021, the year of the crunch COP26 climate talks, this seems surprising – shocking even. But that analysis is already out of date. As winter approaches the number of food companies committing to net zero continues to snowball. Critically, many are realising such a promise is nothing without a plan – a plan that is grounded in science-based targets. Anything less is “blah, blah, blah”, as the climate campaigner Greta Thunberg puts it.

Indeed, brands that end this year thinking net zero makes them a hero could face a long hangover in 2022. Fossil fuels were the focus of COP26 but many experts and campaigners worked tirelessly to get food emissions on the debating table. Food systems are, after all, responsible for 31% (16.5 billion metric tonnes) of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, according to the latest data from the Food and Agriculture Organization.

Commitments on deforestation and methane are welcome but key issues, such as meat and dairy consumption and the role of regenerative agriculture systems in curbing emissions and restoring biodiversity, were ignored. Can the private sector take the lead? Next year will provide some initial answers.

Almost three in four (72%) US buyers say support for regenerative agriculture and protecting soils is important when selecting suppliers, according to the Bord Bia survey. In 2022, expect the big food brands to talk a lot about regenerative or ‘nature-positive’ farming – and for campaigners to start unpicking what, exactly, they mean by it.

But it will be a brave CEO that starts talking about the c-word – consumption – with any conviction. Many speak openly of the shift to plant-based food and drinks but there is no indication (yet) that this means cannibalising the dairy or meat products in their portfolios.

To lead a food company into 2022 won’t be easy. The deep emission reductions required for net zero will be hard to swallow. Shareholders who shout about ESG will need convincing that the early costs of carbon cutting are worth it in the long term. And consumers just want the truth in a convenient format.

Handling the truth

According to a huge Edelman survey recently, chief executives are the least trusted source on climate change (42%). “Put bluntly, CEOs are working from a trust deficit position when it comes to presenting climate policy changes in their business,” the agency said. Only around half of consumers (54%) trust food and beverage companies on climate change action, though that’s above retail (49%) and fashion (43%). They also want to see brands and NGOs collaborate rather than chuck rocks.

There are signs, albeit tentative, that this is beginning to happen – and bear fruit. Take the work being done by the Ellen Macarthur Foundation (EMF) to tackle plastic pollution: 74% of brands, retailers and packaging producers signed up to the global commitment are now publicly disclosing their plastic packaging weight – up from 49% in 2019. An update published this week showed 86% of the food companies involved have put their plastic footprints in print.

It wasn’t all good news, though. FMCG firms are still struggling to integrate reusable packaging into their existing models and incorporate more recycled content into their single-use plastic packaging.

There is an argument that plastic is yesterday’s problem and carbon is today’s; that brands will drop work on packaging and focus on net zero. The two are tied though. Packaging accounts for 24% of PepsiCo’s emissions footprint, for example, and as one of its three largest emissions drivers represents, the company says, a “clear link between climate and our other sustainability activities”.

As some brands have begun to realise, net zero is not like the carbon reduction programmes of days gone by. There will, among manufacturers in particular, be a focus on energy – and switching to renewables – but, as companies begin to work through their indirect (or Scope 3) emissions, attention will turn to new models, new products and new supplier relationships.

Rather than side-line every other aspect of sustainability, a robust plan to tackle climate change could bring it all together. Tough decisions lie ahead, though, as companies grapple to balance their carbon reduction aspirations with work on everything from water consumption and staff welfare to plastic pollution and biodiversity loss.

Low confidence in corporates

Biodiversity and nature will undoubtedly be key issues in the coming months. The production of food is the primary cause of biodiversity loss and pressure to source palm oil and soya in particular from sustainable sources will increase. Boycotts of some products beckon.

Nature-based carbon offsets will also attract more attention; so, too, the concept of offsetting more generally. Critics are easy to find and there is even a chance carbon neutrality, in relying on offsets, could become synonymous with greenwash.

Much is expected of the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Credits – another voluntary scheme. Critics will argue – as ever – that these industry-led agreements are a smokescreen – “a tactic to successfully prevent effective regulation”, as Changing Markets, a campaign group has put it. But if regulation is rubbish or rule makers remain reluctant, then these are all we have got (for now).

Schemes could well be tightened and slackers given short shrift. The Science-Based Targets initiative recently raised the bar with the launch of a net zero corporate standard. Those adopting it must set both near- and long-term science-based targets across all scopes and in line with 1.5°C. Ambitions of under 2°C are fast going out of fashion.

Next year could prove pivotal for voluntary agreements because consumers are twitchy and lack confidence in corporates. They have good reasons. Think of the regular scorecards assessing sustainable palm oil or the missed Consumer Goods Forum’s target to end deforestation by 2020. “Our planet deserves real leadership and time is running out. When and how will the CGF respond?” wrote Global Witness, an international NGO.

This brings to mind a 2010 essay in the Harvard Business Review entitled ‘Leadership in the age of transparency’. “The key to becoming a contemporary corporate leader,” the authors wrote, “is to take on responsibility for externalities – what economists call the impacts you have on the world (like pollution) for which you are not called to account.” Food companies may have avoided any serious regulation spilling from COP26 but this has left them to respond to health, environment and social crises alone. As Dan Crossley from the Food Ethics Council, a UK-based charity, says: “Think extended producer responsibility writ large.”

Main image: Milan, Italy, People protesting against global warming

Credit: Eugenio Marongiu / Shutterstock.com